Union Mills’ Industrial Heritage

Union Mills celebrates its 225th anniversary in 2022, a good opportunity to reflect on the site’s rich industrial history. Founded in 1797 centered on a water-powered gristmill, the site evolved during the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries along with the American Industrial Revolution.

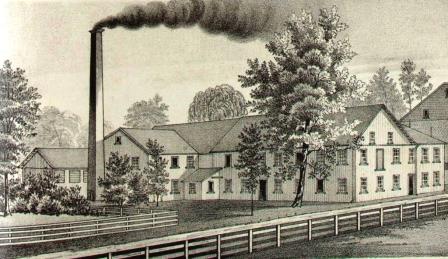

(Image above: The A.K. Shriver & Sons Tannery in 1877, as depicted in the 1877 Illustrated Atlas of Carroll County, Maryland; Lake Griffing & Stevenson, Philadelphia)

Early Site History Focused on Flour Production

In 1797, brothers Andrew and David Shriver, Jr. joined in a business enterprise focused on the production of flour in a water-powered mill. The brothers signed a contract on January 25, 1797, with millwright John Mong, for a “sett of mills” featuring a “Mill for Manufacturing grains into flour.” The contract included specifications that included the latest in milling technology, using machinery designed by Oliver Evans.

In the late 1780s, Evans had invented a method to more efficiently manufacture flour. A key part of Evans’ invention was the innovative use of continuous materials processing, including grain elevators and gravity feeds to move grains and flour through a mill. In 1790, the U.S. Patent Office granted Evans the third U.S. patent ever issued, for his “method of manufacturing flour and meal.” And in 1795, Evans published “The Young Mill-Wright & Millers Guide” to promote his ideas for automated milling technology.

The title page for Oliver Evans’ “Young Mill-wright’s and Miller’s Guide, published in 1795.

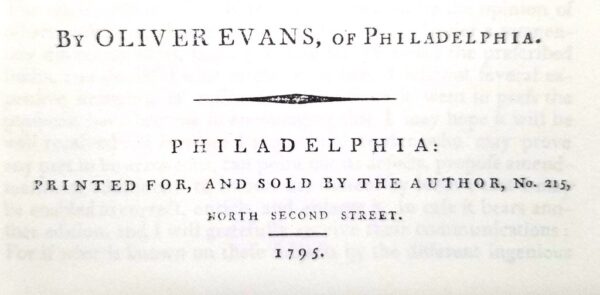

Evans’ book included detailed specifications for an automated water-powered gristmill. Attached to the book were a series of plates, providing detailed drawings of waterwheels, flumes, gears, millstones, grain elevators, and all the machinery required to manufacture flour in the mill. All of the equipment in an Evans mill was water-powered.

A plate from Oliver Evans’ “Young Mill-wright and Miller’s Guide,” depicting an installation of a breast-shot waterwheel and flume, like that at Union Mills.

The Shrivers built their mill using this new technology. The Shrivers’ mill was a large merchant mill that produced flour that they shipped to Baltimore in barrels where the flour was sold world-wide as part of a growing international flour market, In addition to the gristmill, the Shrivers’ enterprise included a sawmill and a number of supporting trades, such as a tannery, blacksmith shop, wheelwright, and cooperage (to make barrels). In addition, the family also farmed, making their operations large self-sustaining.

Expansion of Tanning Operations

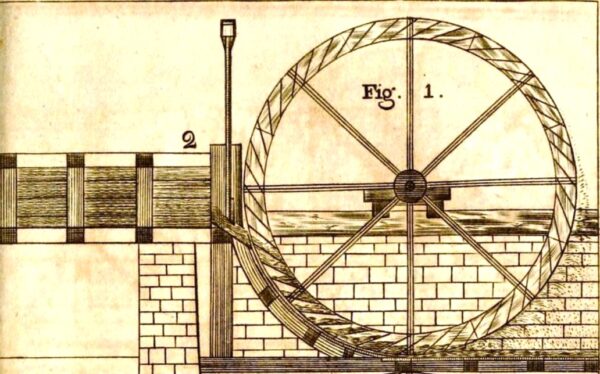

A diagram of the tannery vats in the Union Mills tannery yard in 1827.

At the outset of the Shriver family’s enterprise at Union Mills, the tanning of animal hides to make leather was a supporting trade. Leather was needed for drive belts in the gristmill and also was an important commodity for everyday life. Leather was needed for shoes, clothes, saddles, harnesses, and many other uses.

Over time, leather tanning became a larger and more important industrial operation at Union Mills. By the 1820s the Shriver Tannery had grown in size and the number of hides produced. According to the 1820 U.S. Census, Andrew Shriver’s tannery had 26 vats that processed 400 hides and skins annually, employed two men, and produced shoe and harness leather having value of about $2,000 a year.

An 1827 yard book (shown right) depicts 28 vats at the tannery at Union Mills. Of these vats, 24 were for tanning and 4 were leaches, where tannins were leached from ground oak bark for use in the tanning process.

Leather tanning operations at Union Mills continued to grow, enough that when founder Andrew Shriver died in 1847 two of his sons divided up the families’ businesses. One son (William Shriver) continued operating the mill and another son (A.K. Shriver) took over the tannery.

The A.K. Shriver & Sons Tannery grew the tanning operations, tearing down older log buildings and adding new structures for the production of leather in 1859. That same year they repaired the tanning vats and added new ones.

The A.K. Shriver & Sons Tannery was proud of the leather it produced, and was recognized for the quality of its leather at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The A.K. Shriver family would continue to produce leather at Union Mills until the 1890s.

Evolution to Steam Power

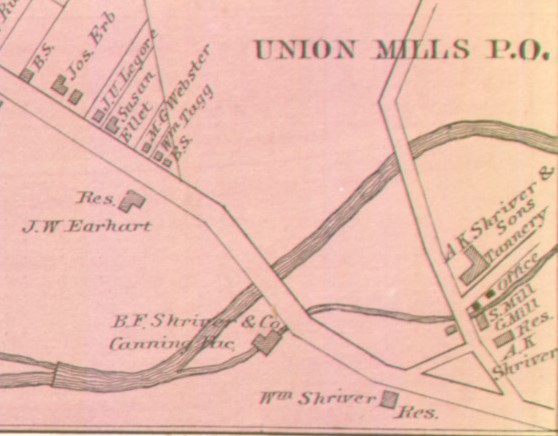

A map of Union Mills from the 1877 Illustrated Atlas of Carroll County, Maryland, showing the site’s grist mill, saw mill, tannery, and cannery.

In the Shriver Tannery’s early days, power to grind bark in the tannery’s bark mill was provided by a horse. Typical for most tanneries of the era, the Shrivers would hitch a horse to a harness and yoke connected to the bark mill, then the horse would walk in circles around the bark mill to power its operation. Additional gears could connect to the bark mill for any other mechanical operations in the tannery.

As the Shrivers modernized their operations, in 1862 they installed new steam boilers and a smokestack. The boilers burned spent tanbark and provided steam power for the tannery’s operations. The boilers not only powered the bark mill but also circulated tanning fluids between the vats. Thus, industrial operations at Union Mills made the jump from horse and waterpower to steam power as the American Industrial Revolution continued to progress.

In 1869, industrial operations at Union Mills continued to evolve when B.F. Shriver, one of William Shriver’s sons, started a canning operation in the Cooper’s Shop behind the gristmill, to preserve excess fruit and vegetables from the family’s farm. The B.F. Shriver Canning Co. rapidly grew, soon moving its operations across Littlestown Pike, over the mill’s tailrace. The B.F. Shriver Canning Co. also would make use of steam in its cannery. B.F. Shriver incorporated steam retorts (pressure cookers) for the processing of canned goods, soon after the retort was invented by his brother Andrew Shriver in 1874. The steam retort (U.S. Patent 149,256) dramatically increased the capacity of canning compared to traditional methods of food preservation, thus making food cheaper and more accessible to an increasingly urban population.

Although tanning at Union Mills ceased in the 1890s, milling continued until the 1940s and canning continued until the mid-twentieth century, reflecting over 150 years of innovative industrial operations at the historic site.

In 2022, the Union Mills Homestead celebrates the 225th year since it was founded in 1797. Celebrate along with us by following along as we look back at the historic site’s unique history, reflecting the six generations of the Shriver family who made the property their home for a period over 160 years.

I am curious to know if there was ever a Union Mill in Spencer, Indiana? Could have been called Sunshine…. 196. I found a metal stencil…. Would like to know history. Thank you